Client Feature: Nasreen Sheikh

Nasreen Sheikh, a national of Nepal, visited our law firm in 2018 to secure a green card. We have since gotten to know her very well and have been incredibly moved by her story. Despite being born in a region that does not record female births and being forced to work in a sweatshop as a child, Nasreen has since become a powerful leader and inspiration for women and girls worldwide. She is now a celebrated advocate for disadvantaged women and victims of sweatshop labor and forced marriages.

We are excited to share her story here.

Passage Immigration Law:

Your story is incredibly powerful. Can you tell us a bit about your childhood and how you came to work and sleep in a Nepali sweatshop at a very young age?

Nasreen:

I was born in a remote village on the border between India and Nepal, where neither birth nor death records are kept. In fact, if you were to ask me how old I am, I couldn’t tell you honestly. Not only are we very economically disadvantaged, we are 100% below the poverty line. We are completely cut off from the world. We exist in a male-dominated society where women have no rights– absolutely no rights. We are not even allowed to laugh out loud because it is considered disrespectful. We are forced into arranged marriages. We become housewives, where at the end of the day there is often abuse. There is torture.

At the beginning, this was very normal to me. That is what I knew. But when I was around six or seven, I started to notice things. I witnessed one of my aunts being murdered by her husband. Just a few months later, he married another girl. This aunt, she was close to my heart. She was loud. She would wear makeup and lipstick. She was a fearless woman. Because of this, her husband was stigmatized by society. This loud woman, who wore makeup and went outside was not good for him. He tried to warn her but she didn’t listen. So, one day he killed her. The whole village knew about her death but never reported it. I was very, very young. When I asked my mother about it, she would say, ‘Let’s not talk about it.’

Then I witnessed one of the most heartbreaking things, my own older sister being forced into marriage. It was not right. I was about 8 when my sister’s marriage was arranged, and she was around 12. I would go out in nature and talk to the tree or the sky or the field. I would ask, ‘What is happening to me? What is happening to my sister?’ I would cry and talk to the universe. I knew that I would be next. I didn’t know what to do. There’s no way you can find help in that village because the police and the whole system is corrupt. They don’t listen to women. Even if women try, there is no one who will help. I was stuck in the village.

I started to write letters back and forth to my cousin, who moved to the city of Kathmandu from my village. Slowly, I got to know what he was doing. After almost six months, at around age 9 or 10, we had formed a close connection. With his support, I got out of the village and moved to the city of Kathmandu.

I think that I first became a child laborer between the ages of 9 and 10 years old. I worked for well-known clothing corporations that used loosely regulated foreign manufacturing. In order to keep up with the corporation’s demands for low cost and fast production, these factories created illegal sweatshops in inner cities using undocumented workers like me.

Six of us lived, worked, and slept in a 10×10 room without a bathroom or clean water. We were forced to work seven days a week for 10 to 12 hours a day, getting paid less than $2 a day. My only bed was the large pile of clothes that I produced each day. At night, I fell asleep on these clothes and dreamt of where they would end up and who would wear them. If you are reading this and do not know who made your clothes, you may be wearing the clothes I sewed as a child.

Passage Immigration Law:

Could you elaborate on how felt “undocumented” from day one, even in your own country of birth?

Nasreen:

Think for a moment and ask yourself what challenges you would face without a Social Security number, driver’s license, passport, marriage certificate, credit cards, or bank account. In what ways would this disempower your life? Could you go to school or travel? Could you obtain proper employment or rent a home? Could you receive medical treatment if you were sick? Could you file a police report? In my society, women and children are expected to be silent in our actions, opinions, and emotions. Not having documents put us completely in the dark.

Passage Immigration Law:

How were you able (or what kinds of things empowered you) to change your narrative so drastically at such a young age? Were there other girls and women around you who wished to do the same? It must have been difficult to find hope and determination given the conditions you were living in.

Nasreen:

I worked for the sweatshop for about two years. At the end, our agent disappeared and took our last month’s salary. I became homeless. I was around 12 years old. My friends wanted me to go back to my village as I was maturing into a woman’s body. I didn’t want to go back. I planned to stay in the city but my friends were worried because many women at my age end up in sex trafficking. I felt completely alone. I didn’t know what to do. I talked to God, to the universe. ‘Why is this happening to me? Why can’t I have shoes? Why can’t I have a book to go to school? At this lowest point, I received help from a stranger and decided to take control of my life. I began to study and found a small room to live in. This began a ten-year period where I studied English, computers, the internet, mathematics, philosophy, religion and the arts. There is an education system in Nepal where they allow you to study at home and be eligible for exams. I studied and took exams and at the same time made handcrafts to support myself.

During this time, I came to understand the value of a quality education. I learned exactly what I needed, which led me to who I am today. Slowly, I also came to understand that our work system is not set up for human happiness. There are millions of women and children still living the same life I lived. I feel I used my power for change instead of being silent.

Passage Immigration Law:

What brought you to the US, and what was your experience entering and existing in this country initially?

Nasreen:

I came to the United States in 2015 for the first time to speak in a women-led conference. It was very shocking for me to visit the United States; I felt I was entering into a completely different dimension. I was very surprised to see women being independent. My experience at the border was very interesting. I was separated through every part of the security check. They were much stricter with me compared to the rest of the people. I remember one time the Department of Homeland Security stopped me and checked all my personal belongings, including my personal notebook. They asked me some questions very aggressively and I felt humiliated. It is not an easy experience for brown people when they enter the United States.

Passage Immigration Law:

How did you find the tools and resources to start your own nonprofit(s) and begin empowering so many women? Did you build LOCWOM & Local Women’s Handicrafts mostly (or completely) on your own?

Nasreen:

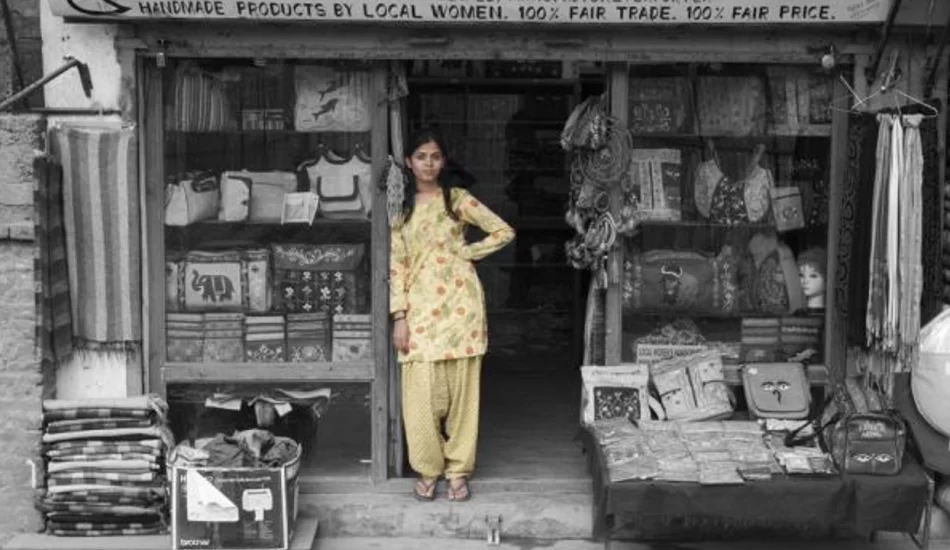

I started L.O.C.W.O.M, Local Organization Comprised of Women Offering Mentorship, a not-for-profit organization based in the United States of America that works to empower women and girls in disadvantaged and vulnerable communities living with poverty and trauma. The LOCWOM USA raises funds and partners with organizations in Nepal and other countries to deliver projects that work towards empowering, educating, and mentoring disadvantaged women and girls. By providing safe spaces, sustainable vocational and entrepreneur skills training, education, mentoring, health care, and resilience building, we aim to provide opportunities to empower women and girls. We hope to help them build confidence and empower them for a positive future and a life without poverty for themselves, their children, and their community.

Passage Immigration Law:

What projects/causes have you been involved with most recently? What do you hope to do with your organization(s) over the next few years and how do you hope to spread your message and promote your cause?

Nasreen:

Our current focus is in Nepal which has a population of 29.6 million with 50.4% female. Nepal is one of the least developed countries in the world and in 2015 suffered a massive 7.8 magnitude earthquake. This caused extreme economic disruption due to political instability. Only 2% percent of women own businesses and unemployment in Nepal is higher than 40 percent. On average, more than 1,500 leave Nepal every day for foreign countries, according to the BBC. Each year 10,000+ women and girls in Nepal are trafficked into the international sex trade. Nepal has the third highest rate of child marriage in the world, and currently has 1.6 million children working in illegal sweatshops.

We hope to raise 500k in funds and partner with a local organization in Nepal to provide support to disadvantaged women and girls. We support disadvantaged women and girls on their journey to empowerment through:

- Providing a safe space in our Empowerment Centers which are also a hub for our programs, and a place to house women’s businesses;

- Providing quality education, vocational skills, and entrepreneur training, as well as education in literacy, numeracy, health care, menstruation health, and environmental sustainability;

- Providing forums for mentoring and collaboration between women;

- Providing basic health care and support to communities to improve health standards and developing reusable menstruation pads for distribution;

- Building community resilience to natural disasters, economic crisis, and the impacts of climate change, and supporting them in times of hardship through emergency relief;

- Reducing the use of plastics through creating alternatives;

- Advocacy for improved women’s rights and a world without child labor, child marriage and human rights violations.